Different ways to imagine Palestine

On the ground, it's war, but in books it's about love, longing and memories.

We Are All Equally Far from Love

We Are All Equally Far from Love begins with a woman falling in love with a man to whom she writes letters, not out of a whim or a choice, but because she is instructed by her boss to do so. Soon they are discussing the weather, and waiting for his letter becomes the most important thing to her. But, one day, they stop coming.

From there the story moves to Afaf, a teenage girl, who works at a local post office and likes letters and keeps them as treasures; a married woman who develops feelings for a physiotherapist that disturbs her conservative life; a shy man who works in a supermarket and cannot bring himself to interact with people; a husband whose desperation to be with his estranged wife leads him to threaten rape; and finally a girl quietly struck by “a tenderness” in her father’s voice for another woman who is not her mother.

The vignettes are so seamlessly tied that one wonders if they are interrelated or separate. The characters overlap with each other in their experiences of love and loneliness and, to an extent, boredom. There is no specific geographical setting (“Palestine” appears only once), which could also be a ploy by the author to escape from the wrath of the war and hide in the inner lives of her protagonists.

Adania Shibli is two-time winner of the Qattan Foundation’s Young Writers’ Award for this work of fiction and her acclaimed novel Touch.

Published in 2012. Translated from the Arabic into English by Paul Starkey.

The Blue Between Sky and Water

What is the blue between sky and water? Is it a space where there are no borders and where the living and the departed come together without fear?

In The Blue Between Sky and Water, a Palestinian family from the 1940s is forced out of their ancestral village in Palestine when Israel was created. They relocate to the Gaza Strip, like so many other refugees, and later spread out across the region – from Cairo to Kuwait and eventually to the US.

But decades later, one of the granddaughters, Nur, returns to Gaza after falling in love with a Palestinian doctor. Her love affair brings about a clash with her traditional relatives: “This is not America where everyone fucks whoever they want whenever they want because it’s fun. This is Gaza. This is an Islamic place.” Gaza is also “the largest open-air prison in the world” where freedom is desired but never granted and where four generation of women including Nur, who form the heart of the novel, move from suffering to resilience, negotiating their way through different continents.

“Abulhawa’s prose is luminous; her control of a complex weaving of narrative voices – young and old, male and female, magical and real – is masterful,” says Margie Orford in Independent on Sunday. This is her second novel and was sold in 19 languages before its release.

Published in 2015.

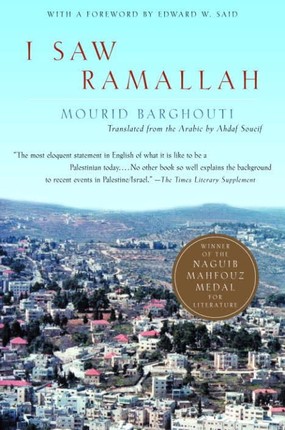

I Saw Ramallah

In 1966, the Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti left his country to return to university in Cairo. In 1967, after the Six-Day War, when he returned, he was barred from entering the country. Thirty years later, after continuous struggle, he was finally allowed to enter Ramallah, his own hometown. This is his autobiography. Edward Said, who wrote the foreword, describes it as “one of the finest existential accounts of Palestinian displacement we now have.”

The bridge that Barghouti crosses as a young man leaving his country is the same bridge that he uses to cross back after thirty years. Apart from that nothing has remained the same, which leads him to the cruel realisation that he has become permanently homeless. He records his impressions and begins to recount stories of his life in Egypt, his subsequent deportation under Sadat, and his existence in Hungary where he lived, worked, and wrote for many years.

One of the distinct aspects of this autobiography that Kin Jensen of the Al Jadid observes is that it is unapologetic about the “normality” and pleasure that a person can experience, even in exile. There is a passage in which Barghouti describes his son Tamim playing in the snow of Hungary. “I used to see what Budapest gave him and say to myself that we owed it to our places of exile to remember the good things, if we did not wish to lie.”

I Saw Ramallah won the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature.

Published in 1997. Translated from the Arabic into English by Ahdaf Soueif, published in 2005.

Palestine

In the graphic un-novel Palestine, a squinting Palestinian boy hunches in the rain while Israeli soldiers, having made him take off his keffiyeh, interrogate him from the shelter of an awning. “Comics have outgrown their superhero underpants,” notes Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow as she interviews cartoonist Joe Sacco, who specialises in one of their most dynamic young subgenres: the political comic book.

“Sacco uses comics to deliver familiar content in an unfamiliar form, disarming us of our numbness to images of war and privation. His focus – preferring the anecdotal to the panoramic – excavates details that seldom make it to the news or the history books.”

Between 1991 and 1992, Sacco immersed himself in the Palestinian existence, “taking notes and drinking endless cups of tea” with the locals and procuring intimate testimonies that the Western media ignored in order to narrate the “bigger picture” to the public. His impetus for going, in his own words, was that he felt the American media had really misportrayed the situation. He grew up thinking of Palestinians as terrorists and it upset him enough to go, and, in a small way, give the Palestinians a voice.

Palestine has been favorably compared to Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus. Originally published in 1993 as a nine-issue comic series, it won the 1996 American Book Award. It was then republished in a single 300-page volume with a new introduction by one of Sacco’s primary influences, Edward Said.

Published in 2001.